背景知识:1906年在英国德文郡(Devon)的普利茅斯市(Plymouth),举办了一场博览会。 大会邀请参观人员凭自己的技巧与判断,猜测一头公牛宰杀后的重量。 为了增加困难度,活动要猜的不是公牛活的时候的重量,而是经过开膛后的重量,也就是扣除头、脚、内脏、毛皮后的重量。 将近800人付了6便士的参赛费。 答案公布后,有一个人完全猜中正确重量,1198磅(约545公斤)。英国著名的统计学家高尔顿(Francis Galton)偶然参与了这次的活动,他在活动结束之后向主办单位要了这800人猜测数字的数据,经过他的分析,他发现了一个惊人的结果,虽然猜测的结果分布非常广泛,但是所有猜测的中位数却落在1207磅(547公斤),偏离真正的重量仅有0.8%。

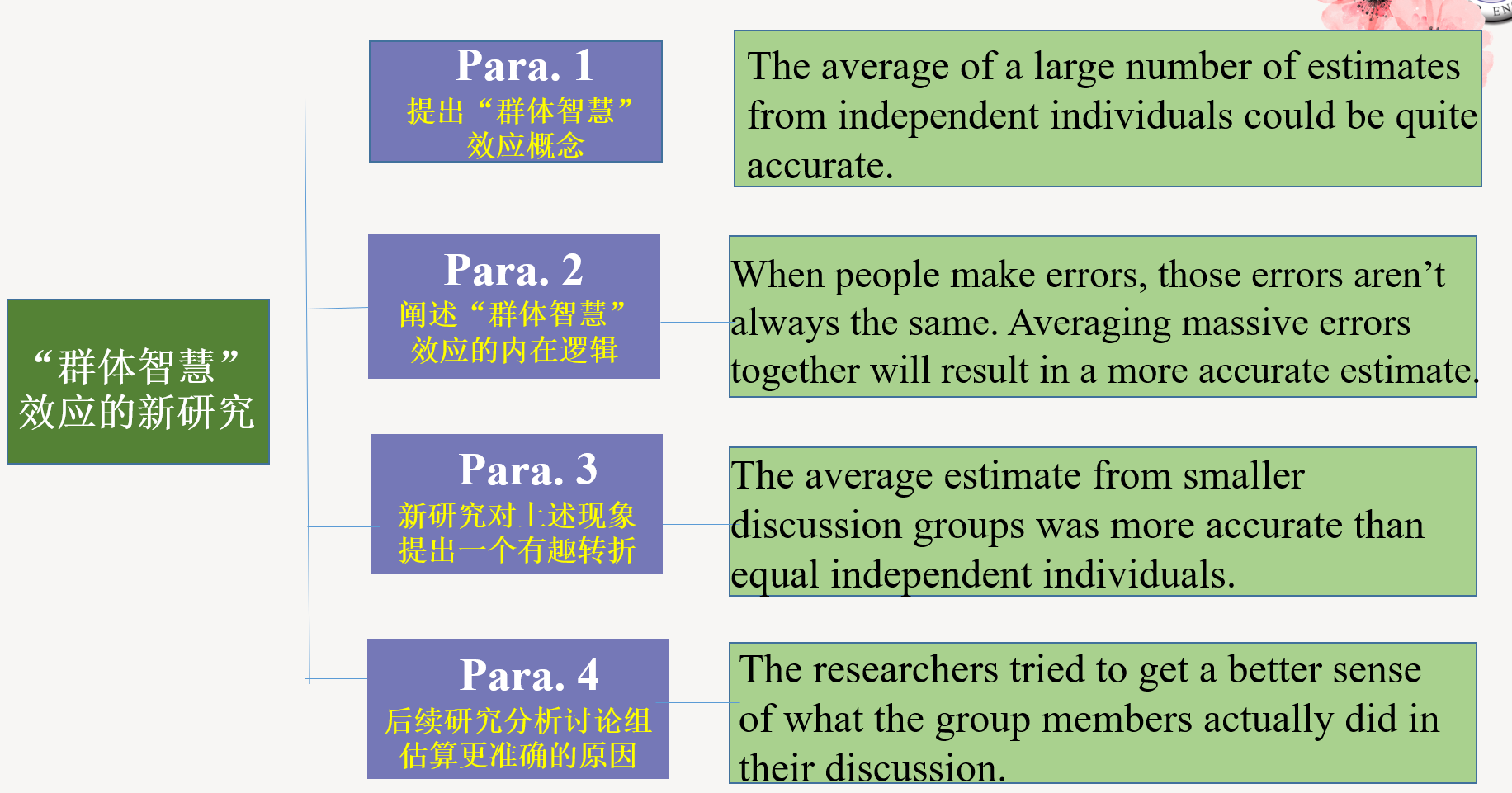

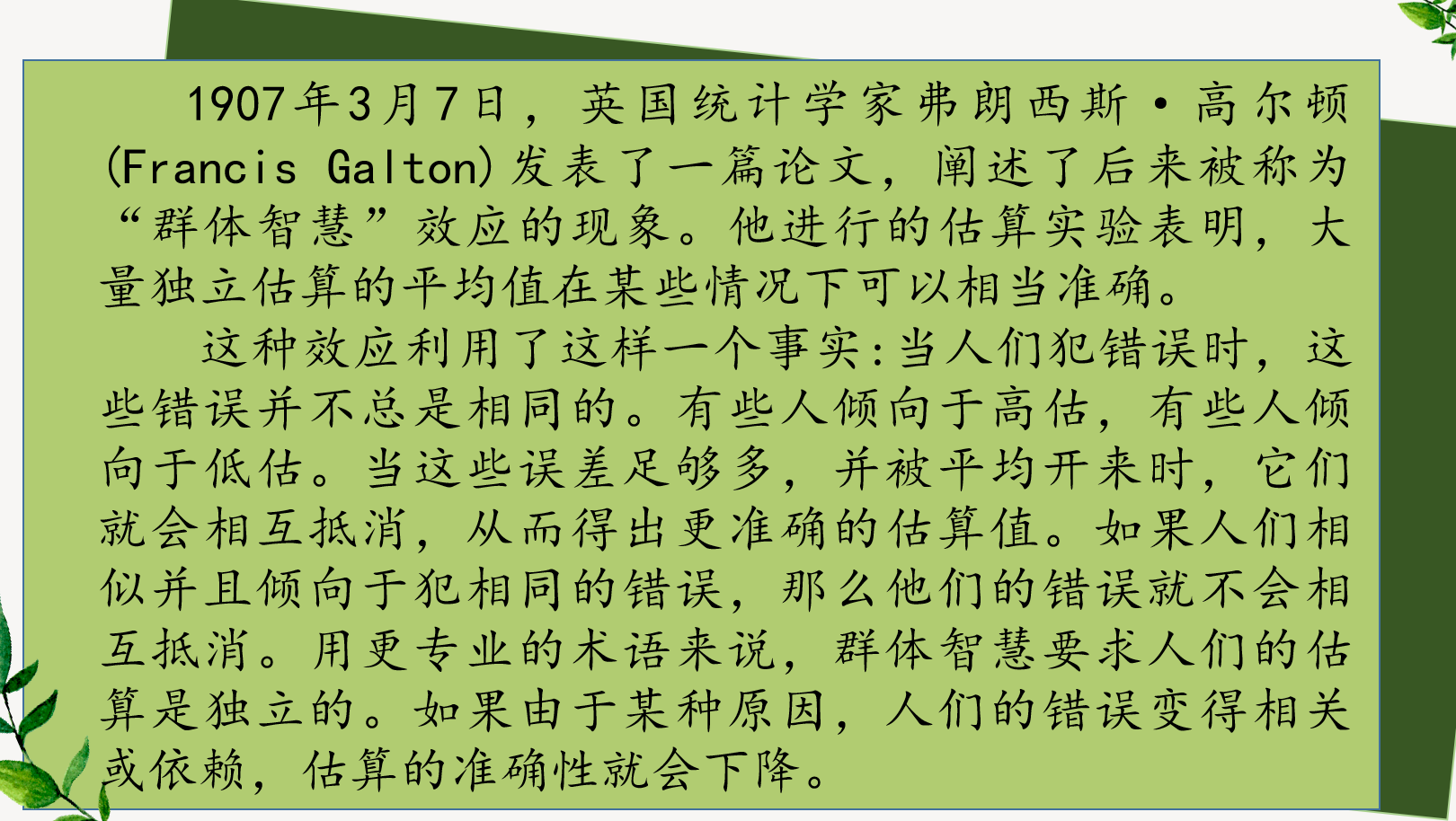

P1 On March 7, 1907, the English statistician Francis Galton published a paper which illustrated what has come to be known as the “wisdom of crowds” effect. The experiment of estimation he conducted showed that in some cases, the average of a large number of independent estimates could be quite accurate.

P2 This effect capitalizes on the fact that when people make errors, those errors aren’t always the same. Some people will tend to overestimate, and some to underestimate. When enough of these errors are averaged together, they cancel each other out, resulting in a more accurate estimate. If people are similar and tend to make the same errors, then their errors won’t cancel each other out. In more technical terms, the wisdom of crowds requires that people’s estimates be independent. If, for whatever reasons, people’s errors become correlated or dependent, the accuracy of the estimate will go down.

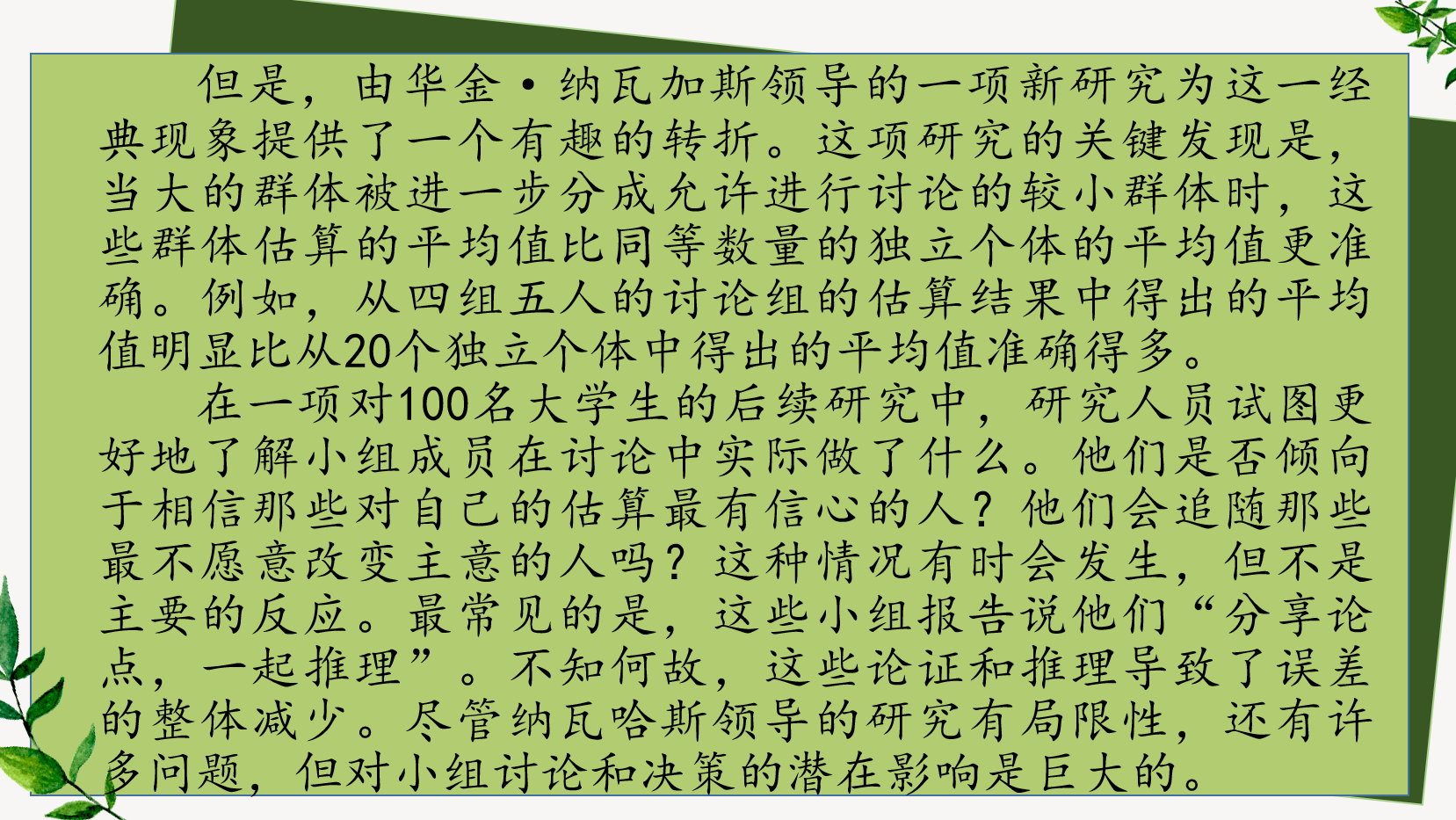

P3 But a new study led by Joaquin Navajas offered an interesting twist (转折) on this classic phenomenon. The key finding of the study was that when crowds were further divided into smaller groups that were allowed to have a discussion, the averages from these groups were more accurate than those from an equal number of independent individuals. For instance, the average obtained from the estimates of four discussion groups of five was significantly more accurate than the average obtained from 20 independent individuals.

P4 In a follow-up study with 100 university students, the researchers tried to get a better sense of what the group members actually did in their discussion. Did they tend to go with those most confident about their estimates? Did they follow those least willing to change their minds? This happened some of the time, but it wasn’t the dominant response. Most frequently, the groups reported that they “shared arguments and reasoned together”. Somehow, these arguments and reasoning resulted in a global reduction in error. Although the studies led by Navajas have limitations and many questions remain, the potential implications for group discussion and decision-making are enormous.